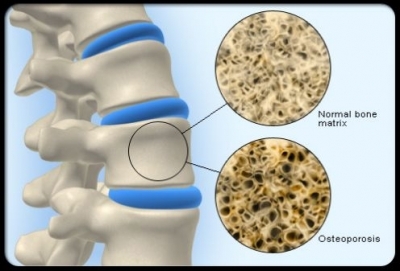

We’re all familiar with the idea – “calcium builds strong bones”. This message comes from everywhere – milk advertisements, a walk down the supplement aisle of any store, and most health magazines. In fact, women over 50 are usually prescribed or recommended to supplement with calcium daily. Even younger women are often encouraged to supplement with calcium during their “bone building” years.

All this concern about bone health is for good reason – if you are a woman, there is a 50% chance you will experience a fracture due to osteoporosis after the age of 50 (1). If you are a man, the chance is around 1 in 4 (1). Even minor bone fractures due to osteoporosis significantly increase risk of mortality (2).

Unfortunately, popping a daily calcium supplement has been shown not to improve bone density, and actually may be HARMFUL.

The Bad News for Calcium

A recently-released meta analysis reviewed 52 studies on calcium intake and bone fracture (27). The analysis showed that dietary calcium intake is not associated with decreased risk of fracture. This research joins a large body of evidence showing that calcium supplementation fails to prevent fracture (3, 4).

These findings are important because the goal with calcium supplementation is not to increase blood levels of calcium. The goal is to increase bone density and, thus, decrease fracture risk. Thus, reviewing the effect of calcium on actual fractures shows the true efficacy of supplementing.

The failing of calcium supplementation to prevent fractures is not to say that calcium is unimportant for bone health. Research does show that women with very low levels of calcium can benefit by increasing intake (5). However, many foods are now fortified with calcium, and most women try to consume more calcium-rich foods on top of that. Most multi-vitamins also contain calcium. So, I would venture to say that few people have very low calcium intake. If you then add a true calcium supplement it’s easy to go well above the recommended range of 1000 – 1300 mg/day for most adults.

…And Even More Bad News

Not only does supplemental calcium fail to prevent fractures, but a large body of evidence now shows it to have adverse effects. For example, a meta analysis evaluating 15 randomized, placebo-controlled trials found that calcium supplementation of at least 500mg/day in patients aged >40 was associated with increased risk of myocardial infarction (MI), or “heart attack” (6). In fact, the NIH has published a review of the literature demonstrating increased risk of cardiovascular disease with calcium supplementation (7). This increased risk of cardiovascular disease is likely related to the accelerated vascular calcification associated with calcium supplementation (8, 9, 10).

Interestingly, a diet with sufficient intake of calcium from food provides a protective effect against cardiovascular disease. As I always say, a whole-foods approach is best.

Cardiovascular disease is not the only risk associated with calcium supplementation. Another recent study found that calcium supplementation increases risk of kidney stone re-occurrence (11). Past studies have also shown that kidney stone risk is significantly increased with calcium and Vitamin D3 supplementation (12). Again, as with calcium and cardiovascular disease, supplementation increases kidney stone risk but intake of calcium-rich foods decreases risk. A whole-foods approach provides benefit, while artificially supplementing increases risk of harm.

And finally, a clinical trial published last month in the New England Journal of Medicine found that supplementing with calcium and vitamin D is NOT protective against colorectal cancer, as previously thought (13). Although epidemiologic data suggests that calcium intake from food provides protection, supplementation does not. I hate to sound like a broken record here, but supplements just aren’t the same thing as real food.

One reason why calcium supplements are theorized to impart less benefit than naturally occurring calcium is that a supplement provides a large, rapidly absorbed bolus. On the other hand, calcium from food is absorbed more slowly and in smaller amounts (14, 15, 16). Our body is programmed to expect a natural exposure of nutrients such as calcium. It is possible that a large ‘spike’ in calcium from a supplement overwhelms the body’s mechanism for metabolizing it, resulting in the research findings of increased vascular calcification and kidney stone recurrence.

Why That Calcium Pill Isn’t Doing Much for You

It’s actually not surprising that high calcium fails to decrease fracture risk. Bone is living tissue with a complex metabolic process for mineralization (“building”).

Example 1 – Vitamin D

For example, the active form of Vitamin D (calcitrol, 1,25(OH)2D) is known to have a strong effect on bone density (a deficiency can result in rickets or osteomalacia). Calcitrol acts both in the gut to increase calcium absorption, and at the bone to mediate bone mineralization (17). Depending on the availability of calcium, the brain, by way of parathyroid hormone (PTH), regulates expression of the Vitamin D receptor (VDR) in both the gut and in osteoblasts (the cells responsible for bone formation) (17). By doing this, the brain uses Vitamin D to either increase OR decrease bone mineralization, depending on the circumstances. This fact has an evolutionary basis – in times of calcium deficit, the body protects the bone by increasing mineralization by way of Vitamin D. Alternatively, in times of calcium excess, the body actually decreases bone mineralization by down-regulating VDR expression. This helps to explain why calcium supplementation can result in a transient decrease of bone density (17).

Thus, calcitrol is essential for regulation bone density. An insufficiency (<30ng/ml) is present in approximately 64% of the general population even higher in the the elderly population (18, 19). Thus, bone mineralization is impaired for a significant portion of the population.

In other words, if someone is deficient in Vitamin D and takes a calcium supplement, they won’t be able to utilize it. Even if a multi-vitamin contains vitamin D, that form will be the inactive form – cholecalciferol, D3 (or D2, which is even harder to utilize and, thus, less beneficial). When these inactive forms of vitamin D are consumed, the body still needs to convert them into cacitrol (the active form). This mechanism is impaired for many, especially the elderly and when sun exposure is low. So, taking vitamin D will not necessarily increase serum levels to the point where calcium is better utilized. Thus, Vitamin D serves as one example of the complexity behind bone mineralization. Simply supplementing with calcium will not benefit bone mineralization if calcitrol is low, and increasing calcitrol is not always a simple matter of supplementing with vitamin D.

Example 2 – Vitamin K2

In another example, Vitamin K2 demonstrates the complex mechanism of bone mineralization. Vitamin K intake was shown in a meta analysis to be negatively associated with bone fractures (20). Higher circulating blood levels have also been associated with reduced fracture risk (21). Conversely, low levels of circulating Vitamin K are associated with increased risk of fracture (22).

These findings relate to the fact that Vitamin K2 modulates the proteins which regulate where calcium is utilized in the body (23) Vitamin K2 controls the calcium-binding activity of important proteins for bone mineralization and maintenance (24). Thus, Vitamin K2 is essential for bone mineralization to occur.

A calcium supplement or even a multi-vitamin rarely contains Vitamin K, especially the K2 form that is important for calcium metabolism (menaquinone). Vitamin K2 intake is very low in the average diet. However, a nutrient-rich diet will include naturally-occurring K2 from sources such as grass-fed butter and beef, egg yolk, chicken breast and liver, and full-fat, grass-fed dairy products. So, people who are eating a “standard American diet” are unlikely to have the ability to utilize supplemental calcium properly, due to a deficiency of vitamin K2.

Vitamins D and K2 provide just two examples of why ensuring bone health is not as simple as supplementing with calcium. These vitamins are often not included in supplements, especially in the correct forms. Also, a standard American diet and low sun exposure further decrease exposure to these important nutrients. Thus, nutrient deficiencies are one large reason why calcium supplementation has not been shown to decrease fracture risk.

How Did We Get This So Wrong?!?

An important thing to remember about calcium is that significant dietary intake from natural sources IS important for bone and cardiovascular health, especially in conjunction with other related nutrients (i.e. Vitamins D, K2, A, and magnesium). As often happens with nutrients, this fact led to a “more is better” mentality, and supplementation became common. Unfortunately, more is not better. When it comes to calcium (and many other nutrients) there is a “sweet spot” of optimal benefit, and the mechanism of action is complex. You can think of it more like a U-shaped graph. Risk is higher with too low OR too high intake, and risk is lower somewhere in-between. Thus, unless someone is highly deficient, a calcium supplement can do more harm than good. Even if calcium intake is very low, increased intake of real foods that naturally contain calcium is ideal.

This gets back to the ancestral perspective that I always discuss – ancient humans had GREAT bone mineral density without any supplements. They ate a nutrient-rich paleo diet, had lots of sun exposure, and were physically active. This is the formula that works!

Beyond Calcium – How to Really Prevent Osteoporosis

By now I hope you’re convinced that you should probably stop supplementing with calcium. This is unless you’ve been clinically tested and prescribed a supplement. Even if your levels are low, real food sources are a safer choice than a supplement. This is especially true because of the increased risk of cardiovascular disease and kidney stones with calcium supplementation.

The good news is that there are many “non-calcium” steps you can take to improve your bone health. These factors are all directly linked to bone health, but are also cornerstones of an ancestral lifestyle. Focusing on these practices will do a lot more for your wellness than just decreasing osteoporosis risk! These steps include:

- Avoid a calcium supplement and even watch for foods that are commonly fortified. These include commercial orange juice, non-dairy milks, breakfast cereals, breads, crackers, and instant oatmeal. Most of these foods aren’t a part of an ancestral diet framework anyway, so you’re not missing out on anything.

- Get calcium from a nutrient rich, whole-foods diet. Good sources include shellfish, avocado, eggs, dark leafy greens, bone-in fish (such as sardines and canned salmon), almonds, yogurt, cheese, oranges, and bone broth. Aim to consume at least 600 milligrams per day from whole food sources.

This chart from Eat Drink Paleo provides an idea of where to get calcium from non-dairy sources (25). If you tolerate organic, full-fat dairy, then you can obviously get a lot of calcium from those foods as well.

- Ensure you consume enough of other nutrients essential for bone health – vitamin D, vitamin K2, vitamin C, magnesium, and collagen. Again, a nutrient-rich, whole-foods diet and lifestyle helps to avoid common deficiencies.

- Follow a “bone-healthy” lifestyle:

- Aim to get at least 7-8 hours sleep per night (melatonin aids mineralization).

- Reduce stress (cortisol impedes mineralization) with activities such as meditation, yoga, or thai chi, and foster a strong social circle.

- Decrease systemic inflammation

- Consume sufficient energy/calories

- Don’t use tobacco

- Avoid excessive alcohol use

- Take a look at your exercise routine. Specifically, weight-bearing exercise and strength training have been shown to impart the strongest benefit to bone health. Activities such as weight lifting, Thai Chi, walking, running, and even squats increase bone density and decrease risk of fracture (26).

Summary

Osteoporosis is incredibly common. It significantly increases risk of bone fracture and mortality. However, scientific evidence shows that taking a calcium supplement does not decrease risk of fracture. It also does not decrease risk of colorectal cancer as previously suggested by epidemiological evidence. In fact, supplementing with calcium poses significant increased risks of cardiovascular disease and kidney stones.

On the other hand, naturally-occurring calcium from a nutrient-rich diet does decrease osteoporosis risk. This is especially true in the presence of other important nutrients, including vitamins A, K2, D, and C, magnesium, and collagen. Other important habits for bone health include weight bearing exercise and strength training, stress reduction, sufficient sleep, tobacco avoidance, limiting alcohol use, and consuming sufficient energy intake.

Not surprisingly, these habits are all consistent with an ancestral lifestyle. Adopting these habits provides health benefits well beyond bone health. Plus, you can live without worrying about taking that calcium pill every day.